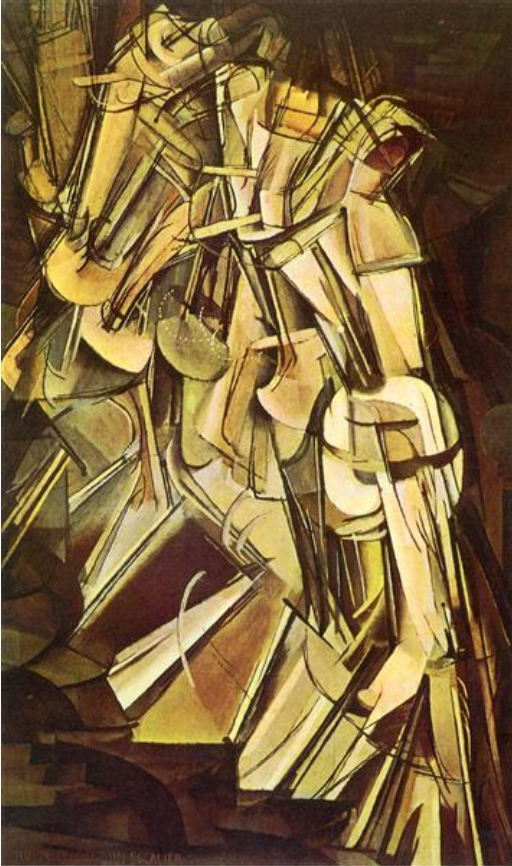

The Opening Gambit It was the year 1913, and a young chess enthusiast moonlighting as an artist made his debut at the avant-garde Armory Show in New York. His opening gambit unfolded rather well. The cubist style painting that he presumptuously called ‘Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2’1 scandalised New Yorkers and soon became the talk of the town. The talented young man was Marcel Duchamp, and his ‘Nude’ didn’t just descend; it stormed its way in and opened the floodgates to the beginnings of Modernism in America.

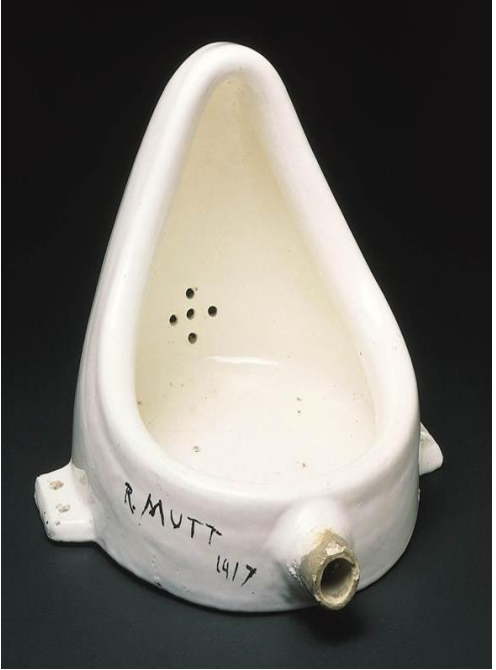

Five years later, history repeated itself. Duchamp submitted a factory-made porcelain urinal signed under the pseudonym R. Mutt to the American Society of Independent Artists. Cleverly rechristened Fountain, the urinal redefined the meaning of art and revolutionised modern art. Nearly a century later, in 2004, Fountain was declared the most influential artwork of all time.

Duchamp was an anarchist at heart or, as the punster in him preferred, an ‘anartist’2. In keeping with the prevailing anti-establishment mood, he challenged the notions of art in a manner that was way ahead of its time. Singlehandedly, he revised the vocabulary of art whose watchword up until this point, had been aestheticism. He set modern art on a tangent, displacing the conventional components of artisanship and aesthetics.

Epigrams, wordplay and humour were an integral part of his work, often underlined with a latent eroticism. His cutting-edge ideas include ready-mades, found art, and engineered kinetic contraptions. However, it is as the founding father of Conceptual Art —art for the mind rather than the eye —that Marcel Duchamp’s strongest influence is felt. It has unquestionably allowed him to play provocateur to legions of young avant-garde artists over the decades.

Nude Descending a Staircase 1912

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, US

Fountain (1917)

Tate Modern, London, UK

The Formative Years Born on July 28, 1887, near Blainville in Normandy, France, Duchamp grew up in a large and loving household steeped in art, music, and literature. After graduating from Académie Julian, he began as a cartoonist and printer before taking up painting full-time. Always hungry for something new, he experimented with the ideas of the Symbolists, especially Odilon Redon, incorporating elements of Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, and Surrealism. He was especially keen on the perception of motion and the depiction of movement seen in chronophotography, as pioneered by Etienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge. Their influence is easily discernible in such works as ‘Sad Young Man on Train’ and ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’.

One can safely say that originality was the keystone of Duchamp’s work. His rapid metamorphosis, from early Impressionist-type paintings to a cubist-inspired period, and then onto ambiguous abstracts and finally onto something no one had ever dared to do before, leaves one in no doubt of his genius. Duchamp’s deep desire to reinvent himself with each work of art and create something without precedent was directly influenced by Raymond Roussel’s play Impressions of Africa. He was now consumed with the idea of creating something original, that would be disturbing as it was hilarious.3 He went to great lengths to protect his originality, even restricting his output so as not to repeat himself. In the period of fifty-two years, he produced a mere thirty pieces.

THE READYMADES

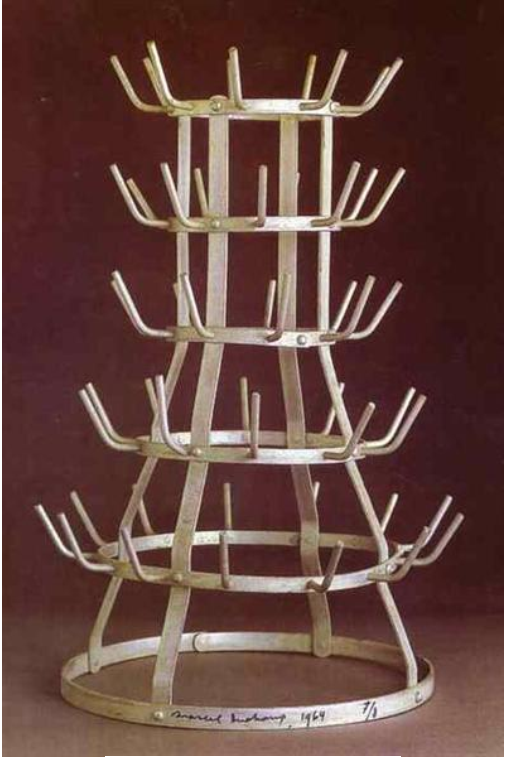

Duchamp realized the futility of painting as early as 1912 when he was merely 25 years old. He gave up the paint brush and during that phase, a substantial body of his work consisted of store bought, mass produced, everyday objects of utility. Duchamp’s ragtag bunch of ubiquitous objects took on an exotic persona when placed in a museum. Granted nirvana from their mundaneness, they were now elevated to the status of objects of art that he called Ready-mades. With this simple act, Duchamp was also able to liberate generations of artists from the stranglehold of aesthetics and artisanship. By chipping away at the very idea of art, eliminating the superfluous, little by little, he attempted get to the crux of the question- what is art4. He got closer to finding an answer to the question that had been nagging him for long- Can one make works of art which are not ‘of art’? This iconoclastic experiment toted up the factor of narcissism that pervades modern art today. The artist became bigger than his art. He was given the artistic license to do what he liked. The work of art could take any form but it was art because the artist said so. With Fountain he effectively proved that anything could be ‘art’5.

The urinal6 was back then an item of curiosity, having recently been introduced to the American public7. He famously joked about how the only works of art America had given were her bridges and plumbing.8Not content with merely presenting the urinal as it was, to the unsuspecting public, Duchamp turned it upside down and with this act annihilated for one, its functional value and also the aesthetic value inherent in an objet d’art. He rechristened it ‘Fountain’ and signed it with a pseudonym- R Mutt; ‘R’ stood for Richard which in French is slang for ‘moneybags’ and Mutt was a variation of JL Mott Ironworks, the company that manufactured the ceramic urinal9.

Arguing his case, he said ‘whether Mr Mutt made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view- creating a new thought for that object’.10

Bottlerack 1914

Private Collection

Hat Rack 1917

Israel Museum, Jerusalem

In Advance of the Broken Arm 1915

With the passage of time, however, the Readymades came to be revered as objects of great artistic value. The irony was not lost on him when he wrote – ‘When I discovered the Ready-made I thought to discourage aesthetics. In Neo-Dada they have taken my ready-made and found aesthetic beauty in them. I threw the bottle-rack and the urinal into their faces as a challenge and now they admire them for their aesthetic beauty.’11 The critique of ‘high art’ and the notions of originality, authorship, and aestheticism that Duchamp had set out to challenge were turned on their head.

The Duchampian Ripple Effect Duchamp’s impact on his contemporaries and later generations was immense. His mechanomorphic forms inspired artists like Francis Picabia and Man Ray, who co-founded New York Dada with him. His influence extended to the Precisionists like Charles Demuth and even Surrealists like Joan Miró and Roberto Matta. Duchamp’s iconic works were constantly reimagined, as seen in Matta’s The Bachelors Twenty Years After and Our Earth is a Target.

Legacy in the Avant-Garde In the 1960s, the Neo-Dadaists revived Duchampian principles. Artists like John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Robert Rauschenberg embraced chance, rejected aesthetics, and highlighted viewer participation. Duchamp’s 1957 lecture, The Creative Act, articulated this belief: “The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world…”

Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing and Cage’s experimental music echo Duchamp’s legacy of iconoclasm. These artists blurred boundaries between disciplines, birthing movements like Fluxus, Nouveau Réalisme, and Arte Povera—all of whom looked to Duchamp as a guiding spirit.

Seeds of Pop and Conceptual Art The Readymades also sowed the seeds for Pop Art and Conceptual Art. Andy Warhol’s Campbell soup tins and Brillo boxes, Sherrie Levine’s bronze urinals, Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn and Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, the infamous banana, all bear Duchamp’s imprint. In India, artists like Subodh Gupta and Shilpa Gupta explore themes and techniques reminiscent of Duchamp’s oeuvre.

Motion, Time, and Play Duchamp’s foray into Kinetic and Interactive Art, such as Bicycle Wheel (1913) and With Hidden Noise (1916), prefigured Op Art and process-based practices. His mail-art piece Unhappy Readymade, executed by his sister Suzanne, anticipated the influence of time and chance on art.

Forever the Provocateur Despite his philosophical outlook, Duchamp never lost his wit or shock value. He was known to tell John Cage he was fifty years ahead of his time—a statement few would dispute. His influence can be seen in the provocations of contemporary artists like Rachel Whiteread, Damien Hirst, and Tracey Emin.

Endgame His final masterstroke was Etant Donnés, a work he laboured on in secret for twenty years, revealed only after his death. With this, he invited audiences to revisit his ideas in a final, enigmatic gesture. Marcel Duchamp reconciled art and life in ways no one before him had dared, fulfilling Apollinaire’s prophecy- ‘Perhaps it will take an artist as remote from aesthetic preoccupations and as preoccupied with energy as Marcel Duchamp to reconcile Art and the people.’

- Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp and co, Terrail Books

- Michele C Cone, French modernisms- Perspectives on Art Before, During and After Vichy, Cambridge University Press

- Harald Szeemann, Marcel Duchamp, Hatje Cantz Publisher

- Bonk, E., 1989. Duchamp, Marcel-Portable Museum: Making of the Boite-en-valise. Thames & Hudson Ltd, London.

- D’Harnoncourt, A., 1973. Marcel Duchamp. Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York.

- Lahiji, N., Friedman, D.S., 1997. Plumbing: Sounding Modern Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press.

- Ramírez, J., 1998. Duchamp: Love and Death, Even. Reaction Books.

- http://www.theartstory.org/artist-duchamp-marcel.html

- http://www.understandingduchamp.com/text.html

- http://www.toutfait.com/unmaking_the_museum/introduction2.html

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/famous-artists/duchamp-marcel.html

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/3671455/Marcel-Duchamp-Art-changed-for-ever.html

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4059997.stm

- http://mediation.centrepompidou.fr/education/ressources/ENS-duchamp_en/ENS-duchamp_en.html

- http://atlassociety.org/students/students-blog/367.1-why-art-became-ugly

- http://hegelmusing.blogspot.in/

- Marcel Duchamp Most Important Art | TheArtStory [WWW Document], n.d. . The Art Story. URL https://www.theartstory.org/artist-duchamp-marcel.htm (accessed 10.28.18).

- Sherrie Levine Most Important Art | TheArtStory [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.theartstory.org/artist-levine-sherrie-artworks.htm (accessed 10.28.18). n.d.

ENDNOTES

1 ‘Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2’, Oil on canvas, 1912, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Accession Number 1950-134-59

2 http://www.toutfait.com/issues/volume2/issue_5/articles/girst2/girst1.html

3 Pg 64, Duchamp and co, Pierre Cabanne, Terrail books

4 Stephen Hicks Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault (Scholargy Publishing, 2004).

5 Pg 115, Duchamp and Co, Pierre Cabanne, Terrail Books

6 Public urinals were developed by Englishman George Jennings and first exhibited in the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London.

7 P 80, Lahiji, N., Friedman, D.S., 1997. Plumbing: Sounding Modern Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press.

8 IBID, Lahiji, N., Friedman, D.S., 1997. Plumbing: Sounding Modern Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press.

9 Marcel Duchamp Most Important Art | TheArtStory [WWW Document], n.d. . The Art Story. URL https://www.theartstory.org/artist-duchamp-marcel.htm (accessed 10.28.18).

10 P 132 D’Harnoncourt, A., 1973. Marcel Duchamp. Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York.

11 Marcel Duchamp Most Important Art | TheArtStory [WWW Document], n.d. . The Art Story. URL https://www.theartstory.org/artist-duchamp-marcel.htm (accessed 10.28.18).

very well written. beautiful site.