A comparative study of Mughal and Rajput miniature traditions

Krishna Holds Up Mount Govardhan to Shelter the Villagers of Braj

Folio from a Harivamsa. (ca. 1590–95)

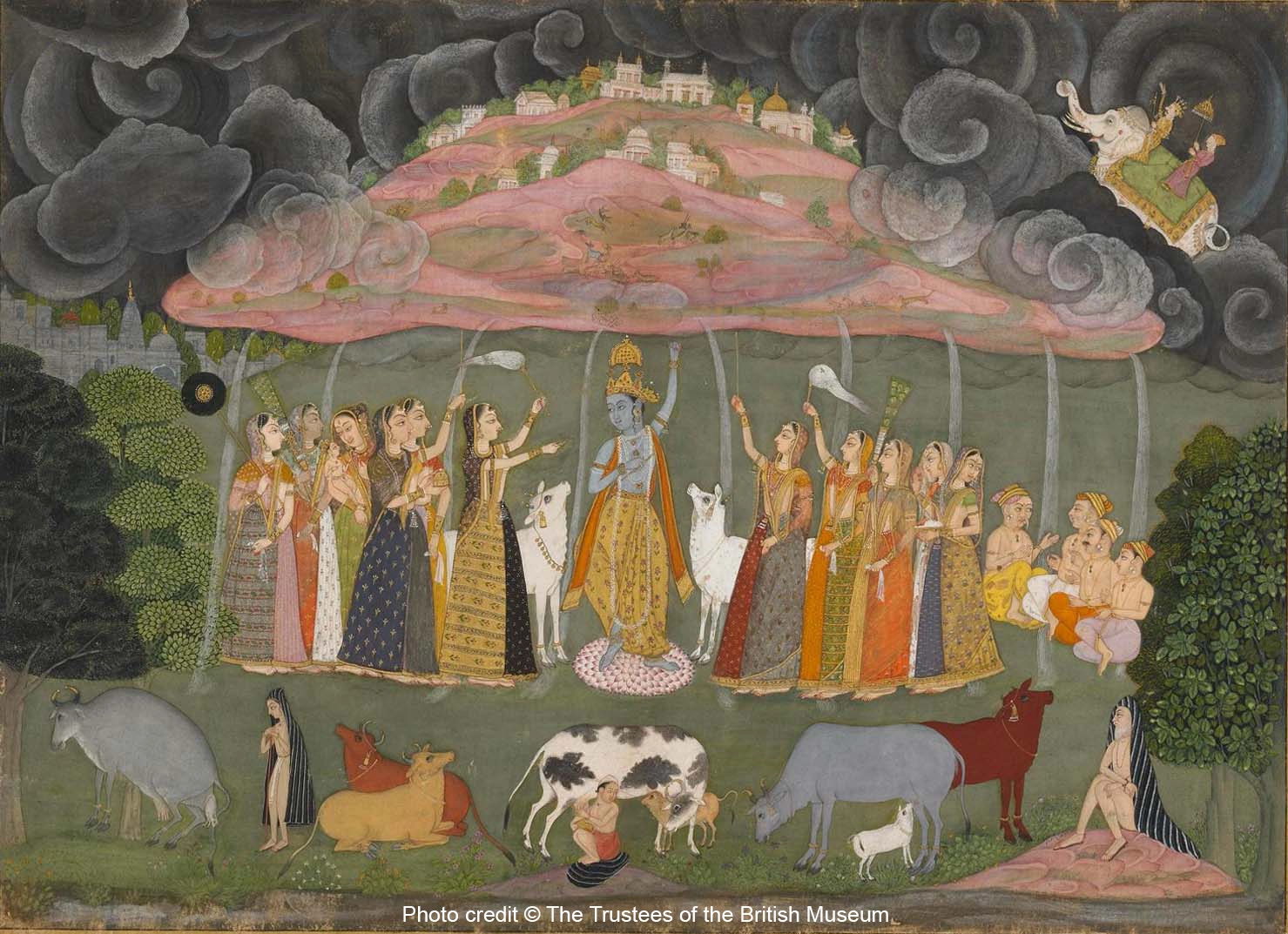

Krishna Lifting Mount Govardhan

Folio from a Bhagawata Purana manuscript (ca. 1690)

Krishna, or the dark one, easily the most idolised God of the Hindu pantheon, was the protagonist of several literary texts such as the Mahabharata, Bhagavad Gita, Harivamsa, and the Bhagavat Puranas. The most human of all Gods, a God of many moods and facets, one who was equally at ease in the guise of a simple cowherd or a gallant warrior; Krishna revelled in his role as a quintessential lover and just as easily slipped into the role of a Machiavellian statesman. In art, his protean personality made him a popular muse, inspiring generations of artists. Mythological events associated with the cult of Krishna became a common theme of representation.

One such legend was ‘Krishna lifting Mount Govardhan’, as recounted in the Bhagavata Purana. Let us examine two visual retellings of that episode—one from the Mughal atelier of Akbar attributed to the painter Miskina, and another from the Rajput tradition by Ustad Sahibdin, likely painted in a Bikaner workshop. Despite the apparent commonality of theme and narrative tradition, their treatment of the subject diverges significantly in composition, style, and visual affect, offering a valuable lens into the differing aesthetics of the two schools.

The Myth Recounted

According to the Bhagwata Purana, Krishna forbade the villagers of Gokula from worshipping Indra, the King of Gods and advised them to worship Mount Govardhan instead, as it was the mountain that provided them sustenance. Incensed by this insult, Indra unleashed clouds that poured torrential rain upon the hapless villagers. An adolescent Krishna plucked out the entire mountain and held it up like an umbrella to shelter his petrified kinsmen. After seven days and seven nights, Indra finally relented and recalled the rainclouds1. Both paintings successfully portray the event with eloquence.

Mughal Naturalism and Dramatic Realism

Miskina’s painting, created in Akbar’s cosmopolitan atelier, exemplifies the Mughal preoccupation with naturalistic detail and psychological veracity. The composition is vertically oriented and tightly constructed, heightening the sense of urgency. Dark, charcoal-grey skies mirror the emotional tenor of the scene.

Trees sway wildly in the storm while startled antelopes run for cover from Indra’s fury. Under the umbrella of the mountain, townsfolk look around nervously, clutching on to their meagre belongings; there are women, crying babies, merchants as well as mendicants, and a menagerie of cows and goats; all taking refuge with Lord Krishna, who stands in the eye of the storm, radiating calm with his electric presence. The detailing of drapery, facial expressions, and the jagged, Persianate rendering of the rocky mountain underscore the Mughal interest in observation and anatomical accuracy, influenced in part by European prints circulating in the court.

Rajput Stylisation and Bhakti Serenity

In contrast, the Rajput miniature by Ustad Sahibdin presents a vision of divine protection suffused with calm and pastoral charm. Though executed in a horizontal format typical of Rajput manuscripts (recalling the older palm-leaf manuscripts), the work integrates certain Mughal influences, particularly in the modelling of terrain and the atmospheric washes that create a sense of landscape depth. Yet the idiom remains distinctly Rajput in sensibility. The scene is marked less by tension than by devotional intimacy.

Krishna is serenely poised atop a lotus pedestal, striking a dancer’s pose. The gopis gather around him, bearing gifts, unfazed by the downpour. The composition includes charming vignettes—a cow mid-birth, a cowherd looking on in awe, and a cascade of vibrantly patterned skirts and jewellery—all rendered in the flattened, stylised manner of the Western Indian tradition.

Shared Techniques, Divergent Visions

Both works employ opaque watercolour on wasli, meticulously prepared paper burnished to a smooth surface, and pigments derived from mineral sources—such as orpiment for yellow, cinnabar for red, copper salts for green and lapis lazuli for blue2 and mixed with gum Arabic. They were also obtained from organic sources; red from lac insect, indigo for blue and the famous Indian yellow called Peori, extracted from the urine of cows fed on mango leaves. The similarity in technique can be attributed to the fact that most painters in Rajput courts had worked in Mughal studios before, including Sahibdin. There had been an exodus of minor painters from the court of Jehangir, who released them, preferring a more intimate number of highly specialised artists3. Nevertheless, the pictorial effect diverges sharply. Miskina’s palette is muted and dramatic, intensifying the sombre mood. Sahibdin, by contrast, deploys unexpected hues—mauve, candy-pink, moss green—that create a dreamlike, almost fairytale atmosphere. His stylisation is not a limitation but a choice, offering an affective register of devotion rather than naturalism.

Two Modes of Seeing

These two paintings, though separated by courtly conventions, aesthetic philosophy, and regional priorities, succeed in reanimating a shared narrative with remarkable sensitivity.

It is fascinating how different schools of art interact and interface with each other, draw from a potpourri of styles and work out a distinctive idiom they can call their own. Most certainly, all traditions have their admirers who identify with and derive a sense of pleasure from them. The Mughal painting stands out for its grim representation of the event. Though technically sound, it comes out lacking in soul. With the calm that the Rajasthani miniature conveys, the idea of refuge in the supreme being is advocated. It is successfully able to capture the spiritual expression which is truly the essence of Indian art.

- B. N. Goswamy, The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 101 Great Works, 1100–1900

- J. C. Harle, The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent

- T. Richard Blurton, Hindu Art, British Museum Press

- Michael Wheeler, “Colour and Technique in Indian Miniature Paintings,” Prahlad Bubbar Gallery

- Oxford Art Online, “Indian Painting, Mughal”

- J. M. Rogers, Mughal Miniatures, British Museum Press

Endnotes

1 B. N. Goswamy, The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 101 Great Works 1100-1900 (Gurgaon, Haryana,

India: Allen Lane, 2014), p. 197.

2 J. M. Rogers, Mughal Miniatures, 2 edition (London: British Museum Press, 2006), p. 21.

3 ‘Indian Painting, Mughal’ <oxford art online> .

Yes. Enjoyed the read.

Capture of fury and unease Vs serenity in approach.

Also, memory refreshed of the Krishna – Govardhan episode esp since i recently visited Govardhan but had forgotten the context !!

Splendid! Very interesting and informative.